Continuing from where we left off in Part 5, lets start exploring the Penetration Tests for the Cloud Environment in this post.

D. Penetration Tests for the Cloud Environment

Penetration tests (Pen-tests), in this context, mean a set of methods to evaluate the security of the web application by simulating attacks against it before and after deploying the application on the public cloud. By testing the application for vulnerabilities before deploying the application on the cloud, we know how secure the web application is against those attacks. This will help set the baseline. By testing the web application after deploying it on the cloud, we can compare against the baseline to determine whether the cloud environment needs to be tweaked further or not.

Black, white, and gray box testing methods enable the security team and/or the development team with assessing the security posture of the web application [29].

1) Black Box Testing

This testing method does not assume that the performer of these tests know the inner workings of the web applications in terms of its architecture, design, and code structures employed. When testing Commercial Off The Shelf (COTS) applications, employing a set of black box testing methods such as the use of automated scanning tools and manual penetration tests would help the team in assessing the security posture of the application.

2) White Box Testing

This testing method assumes that the performer of the tests know the inner workings of the web application in terms of its architecture and design. It also assumes that the performer of the test has access to the source code of the web application. Tests such as static code analysis, code crawlers, and debuggers are employed in this type of testing.

3) Gray Box Testing

This testing method combines the strength of both black and white box-testing methods and assumes that the performer of the test has a little background of the web application in terms of architecture and design aspects and has access to the source code of the application. For example, taking the amount of external frameworks used to build the web application these days – ESAPI for security, “Spring” framework for presentation and data layers etc. – the development team and the security team know only a portion of the web application. Therefore, employing gray box testing methods make a lot of sense.

4) Selecting a testing framework

The selection of one method over another depends the following factors:

- Time allocated to the Pen-test

- Access to architecture, design, and code structures

- Availability of the security experts

- Goals of the test

To assess the short-term effects of attackers with limited resources, the performer could decide to employ black box testing methods. On the other hand, to study the long-term effects of attackers with significant resources, the performer could decide to employ the gray box testing methods. Therefore, the selection really depends on the situation and the stipulated constraints as stated above.

OWASP testing guide has defined ten different categories of penetration testing to find vulnerabilities in web applications as follows:

- Information Gathering

- Configuration management Testing

- Business Logic Testing

- Authentication Testing

- Authorization Testing

- Session Management Testing

- Data Validation Testing

- Testing for Denial of Service

- Web Services Testing

- Ajax Testing

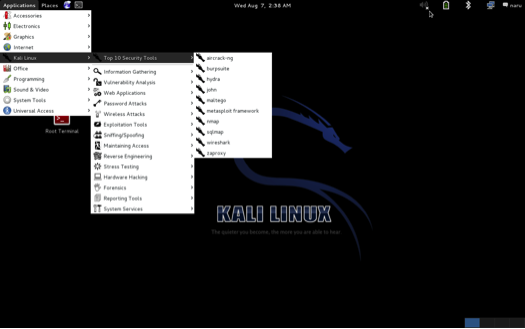

The security team could employ tools such as Kali Linux along with a whole host of security tools that come with it to successfully assess the security posture of the Web application. Kali Linux ships with a wide variety of security pen-test tools as shown in the screenshot below:

Before using any of these toolkits, it is mandatory to seek the written authorization from the CISO and/or the CIO of the organization. These pen-tests have to be run under the direct supervision or guidance of the CISO and/or the CIO. In some cases, the cloud broker or the provider has to clear the tests if performed against the cloud installations. Since the use or misuse of some of these tools would most probably result in property damages including the modification and/or destruction of data.

V. CONCLUSION

As explored in Part 1, Part 2, Part 3, Part 4, Part 5, there are several security implications to moving corporate web applications to the public cloud. There are threats like data breaches originating from the use of shared technology environments and multi-tenancy models of the cloud platform. At the same time, the public cloud-computing platform cannot be ignored due to a false sense of security. Therefore, employing a solid risk management framework such as the NIST’s Cloud Risk Management Framework (CRMF) helps in identifying risks and ultimately validating the selection of security components and controls for a given set of risks.

The CRMF along with the CSA’s Trusted Cloud Initiative Reference Architecture (TCI-RA) identify the cloud actors that are responsible for those security components/controls. The clear delineation of responsibilities enhances the cloud consumer’s transparency and results in crafting a Service Level Agreement (SLA) that would work for all the cloud agents in question. One of the biggest responsibilities of a cloud consumer in moving to the public cloud is to inject “security” into the Software Development Life Cycle (SDLC). This secured SDLC (SSDLC) will enable the consumer to thwart security threats that originate at the application layer.

Employing security-focused stories and tasks enable an Agile Scrum team to pay a close attention to security aspects right from the Sprint planning to code implementation and testing. The SAFECode guidelines will help the development, QA, and security teams in creating a SSDLC platform that would make the engineering of security-aware web applications possible. In addition to following a SSDLC constructs, the use of security frameworks such as ESAPI reduces the implementation time of the security controls.

After the web application is built according to specifications, black, white, and gray box testing methods could be performed to assess the security posture of the web application. Several open source tools such as Kali Linux could be used to successfully perform those testing methods. Before performing any of these types of penetration tests, it is mandatory to get the written authorization from the CISO and/or the CIO. In some cases, it is necessary to get authorization from the cloud agent as well.

[1] NIST. (2011). The NIST Definition of Cloud Computing. Available: http://csrc.nist.gov/publications/nistpubs/800-145/SP800-145.pdf

[2] B. Lyons. (2011). Applying a Holistic Defense-in-Depth approach to the Cloud. Available: http://www.niksun.com/presentations/day1/NIKSUN_WWSMC_July25_BarryLyons.pdf

[3] NIST. (2011). NIST Cloud Computing Reference Architecture. Available: http://www.nist.gov/customcf/get_pdf.cfm?pub_id=909505

[4] CSA. (2011). Security Guidance for Critical Areas of Focus in Cloud Computing V3.0 : Cloud Security Alliance. Available: https://cloudsecurityalliance.org/download/security-guidance-for-critical-areas-of-focus-in-cloud-computing-v3

[5] A. Desai. (2011). What is virtual machine (VM)? - Definition from WhatIs.com. Available: http://searchservervirtualization.techtarget.com/definition/virtual-machine

[6] CSA. (2013). The Notorious Nine: Cloud Computing Top Threats in 2013 : Cloud Security Alliance. Available: https://cloudsecurityalliance.org/download/the-notorious-nine-cloud-computing-top-threats-in-2013

[7] Y. Zhang, A. Juels, M. K. Reiter, and T. Ristenpart. (2012). Cross-VM side channels and their use to extract private keys. Available: http://doi.acm.org/10.1145/2382196.2382230

[8] M. Schwartz. (2012). New Virtualization Vulnerability Allows Escape To Hypervisor Attacks – InformationWeek. Available: http://www.informationweek.com/news/security/app-security/240001996

[9] S. Chauhan. (2012). Virtualization Security: Hacking VMware with VASTO. Available: http://resources.infosecinstitute.com/virtualization-security

[10] OWASP. (2013). Category:OWASP WebGoat Project - OWASP. Available: https://http://www.owasp.org/index.php/Category:OWASP_WebGoat_Project

[11] OSA, “SP-011: Cloud Computing Pattern,” ed, 2013.

[12] NIST. (2011). Guidelines on Security and Privacy in Public Cloud Computing. Available: http://www.nist.gov/customcf/get_pdf.cfm?pub_id=909494

[13] NIST. (2011). NIST Cloud Computing Security Reference Architecture (DRAFT). Available: http://collaborate.nist.gov/twiki-cloud-computing/pub/

CloudComputing/CloudSecurity/NIST_Security_Reference_Architecture_2013.05.15_v1.0.pdf

[14] CSA. (2012). Cloud Controls Matrix v1.4 : Cloud Security Alliance. Available: https://cloudsecurityalliance.org/download/cloud-controls-matrix-v1-4

[15] B. Damele. (2009). Advanced SQL injection to operating system full control. Available: https://http://www.owasp.org/images/d/dc/AppsecEU09-Damele-A-G-Advanced-SQL-injection-slides.pdf

[16] T. Shimeall. (2013). Tactics and Penetration Testing. Available: https://blackboard.andrew.cmu.edu/bbcswebdav/pid-449058-dt-content-rid-3403035_1/xid-3403035_1

[17] T. Shimeall. (2013). Web Hacking. Available: https://blackboard.andrew.cmu.edu/bbcswebdav/pid-449052-dt-content-rid-3403026_1/xid-3403026_1

[18] T. Shimeall. (2013). Strategy. Available: https://blackboard.andrew.cmu.edu/bbcswebdav/pid-449058-dt-content-rid-3403035_1/xid-3403035_1

[19] NIST. (2008). Volume I: Guide for Mapping Types of Information and Information Systems to Security Categories. Available: http://csrc.nist.gov/publications/nistpubs/800-60-rev1/SP800-60_Vol1-Rev1.pdf

[20] NIST. (2006). Minimum Security Requirements for Federal Information and Information Systems Available: http://csrc.nist.gov/publications/fips/fips200/FIPS-200-final-march.pdf

[21] NIST. (2013). NIST Cloud Computing Reference Architecture Cloud Service Metrics Description. Available: http://collaborate.nist.gov/twiki-cloud-computing/pub/CloudComputing/RATax_CloudMetrics_WAs_Docs/RATAX-CloudServiceMetricsDescription-DRAFT-20130621.pdf

[22] SAFECode. (2012). Practical Security Stories and Security Tasks for Agile Development Environments. Available: http://www.safecode.org/publications/SAFECode_Agile_Dev_Security0712.pdf

[23] J. Rockwood, “Choose Your Weapon Wisely: A handbook for determining the right software development method best suited for your team, client, and project (Independent Study Paper). Pittsburgh, PA: School of Computer Science, Carnegie Mellon University,” 2011.

[24] H. Kniberg. (2007). Scrum and XP from the Tenches - How we do Scrum. Available: http://infoq.com/minibooks/scrum-xpfrom-the-trenches

[25] M. Hüttermann, Agile ALM : lightweight tools and Agile strategies. Shelter Island, N.Y.: Manning, 2012.

[26] SecurityNinja. (2009). Secure Development. Available: http://www.securityninja.co.uk/secure-development

[27] OWASP. (2013). Projects/OWASP Java Encoder Project - OWASP. Available: https://http://www.owasp.org/index.php/Projects/OWASP_Java_Encoder_Project

[28] OWASP, “Category:OWASP Enterprise Security API - OWASP,” ed, 2013.

[29] D. Cornell. (2013). Web application testing: The difference between black, gray and white box testing. Available: http://searchsoftwarequality.techtarget.com/tip/Web-application-testing-The-difference-between-black-gray-and-white-box-testing