Continuing from where we left off in Part 1, lets start exploring the risk management framework for a little more in this post.

III. RISK MANAGEMENT FRAMEWORK

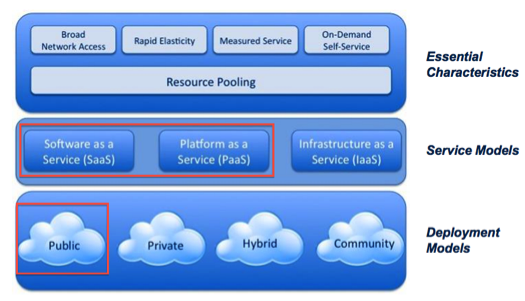

Since the actors, outlined in Part 1 - Roles and Responsibilities, have varying degrees of ownership and influence in the cloud space, establishing security controls becomes a shared or split responsibility among the actors. From the cloud consumer’s angle, security should not be an impediment to embracing public cloud solutions. With that idea in mind, the risk management framework provides a step-by-step approach to identifying and documenting risks in general and validating as to what are acceptable risks to a consumer in relation to the compliance model, so that the cloud consumer can place a level of confidence in moving all the acceptable web applications/systems to the public cloud.

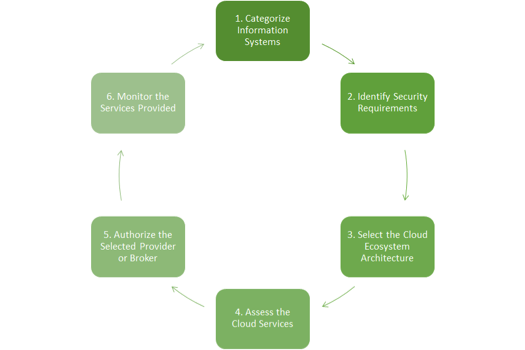

The following diagram shows the NIST’s cloud-adapted risk management framework (CRMF)[13]:

1) Categorize Information Systems

This step enables organizations to consistently map the security impact levels to the types of information and information systems. The type of information includes private, confidential, sensitive etc. The type of information systems includes mission critical, mission support etc. An information system processes one or more information types as input, output, and/or for internal needs.

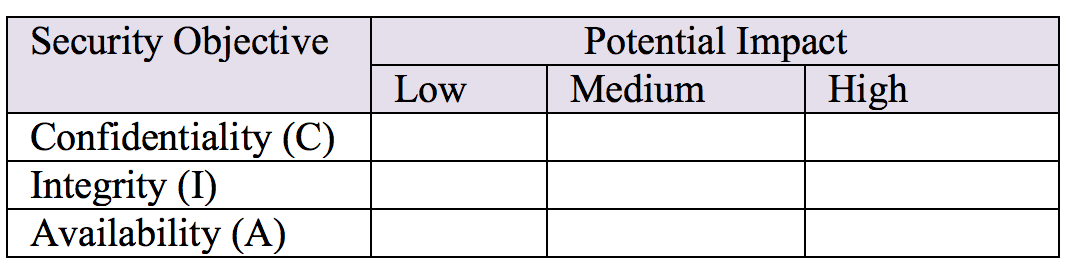

The security objectives and the potential losses for information and information systems could be broadly classified in terms of the classical security goals as follows [19]:

a) Confidentiality

A loss of confidentiality is the unauthorized disclosure of information.

b) Integrity

A loss of integrity is the unauthorized modification or destruction of information.

c) Availability

A loss of availability is the disruption of access to or use of information or information systems.

Potential impact to an organization in case of a security breach could be modeled in terms of low, medium, and high ratings.

a) Low Impact

At this impact level, the loss of confidentiality, integrity, and availability would not impact the primary business objectives of the organization. There will be some degradation in mission capability and minor damage to organizational assets, but this would not stop the organization from meeting its objectives.

b) Medium Impact

At this impact level, the loss of confidentiality, integrity, and availability would impact the primary business objectives of the organization. There will be significant degradation in mission capability and significant damage to organizational assets and/or operations.

c) High Impact

At this impact level, the loss of confidentiality, integrity, and availability would severely impact the primary business objectives of the organization. There will be major degradation or loss of mission capability and major damage or loss of organizational assets and/or operations.

One way to identify information types could be based on the lines of businesses of an organization. For example, lines of businesses could include marketing, sales, manufacturing, R&D, learning & performance, dealer management etc.

Since every organization has a set of resource management areas such as information technology & management, human resources management, and financial management, care must be taken to include such resource management functions and their information types as well. For example, some of the information types within the human resources management function could be HR strategy, staff acquisition, employee performance mgmt., employee relation, benefits mgmt., and compensation mgmt., etc.

Once the information types and information systems are identified, the next step is to assign potential impact of compromises to confidentiality, integrity, and availability as outlined in the following table:

For example, the information type of an organization’s corporate website for public consumption does not have any confidentiality requirement because everything on the website is for public consumption. Therefore, the security category could be defined in terms of the C/I/A triad as follows:

After assigning security categories to all the information types that belong to a business area or a resource management function, all the information systems that support those functions must be mapped to those information types. This is a required step to aggregate the security category at the information system level. For example, a web-based contract renewal system could process two information types as follows:

The resulting aggregate security category for the information system will be the maximum of the above two categories in each of the C/I/A triad as follows:

When aggregating security categories, it is also beneficial to understand the context of the information system in relation to other systems – standalone, connected process flow etc. Without understanding the overall context, assignment of security categories could be erroneous.

At the end of step 1, categorization of information systems, the organization must have a spreadsheet with all the information systems that are being evaluated for the suitability of moving over to the public cloud. This spreadsheet will contain all web-based information systems and their aggregate security categories mapped to their business area or resource management functional area.

2) Identify Security Requirements

NIST defines seventeen security-related areas with regard to protecting the confidentiality, integrity, and availability of information systems and the information processed, stored, and/or transmitted by those systems [20]. Those security-related areas are access control, audit and availability, certification, configuration management, contingency planning, identification and authentication, incident response, maintenance, media protection, physical and environment protection, planning, personnel security, risk assessment, systems and services acquisition, system and communications protection, system and information integrity.

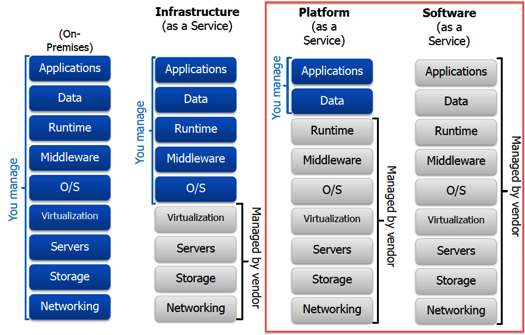

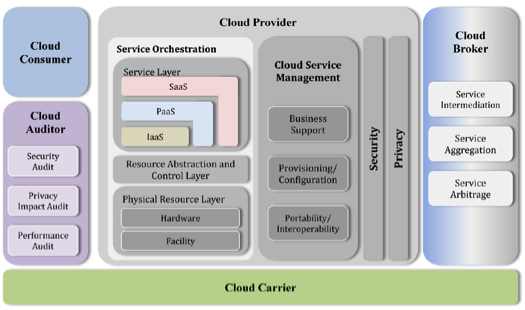

In the case of PaaS and SaaS, the majority of the selection of the security controls falls under the cloud agents such as the cloud provider, cloud broker, and cloud carrier. These cloud actors are required to address the cloud consumer’s areas of concerns as proposed by the NIST’s Security Reference Architecture [13] as follows:

- Risk Management

- Risk analysis

- Risk Assessments

- Vulnerability assessment

- Incident reporting and response

- Business Continuity

- Disaster recovery plans

- Recovery plans

- Recovery Point Objective (RPO)

- Recovery Time Objective (RTO)

- Physical Security

- Physical and environmental security policy

- Contingency plan

- Emergency response plan

- Facility layout

- Security Infrastructure

- Human Resources

- Visual inspection of the facility

- User account termination procedures

- Compliance with National and International/Industry standards on security

- Transparent view of the security posture of the cloud provider, cloud broker, and the cloud carriers.

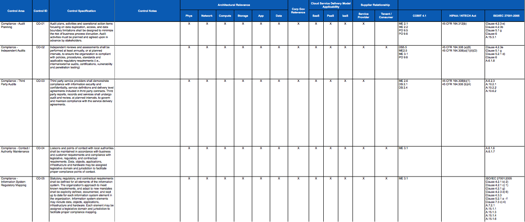

The good news is that an organization does not have to spend the time and money to create the combination of security components and how they map to responsibilities of various cloud actors from scratch. The CSA provides a comprehensive cloud control matrix based on the Trusted Cloud Initiative Reference Architecture (TCI-RA) as shown below:

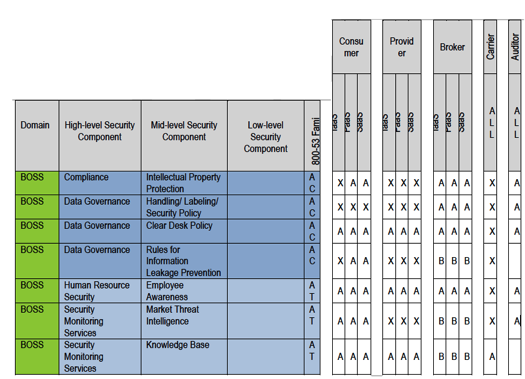

This excel sheet can be downloaded from [14]. What is good about this excel sheet is that it spells out the responsibility for establishing security controls among the various cloud actors. The NIST Security Reference Architecture (SRA) has adopted the TCI-RA and has created 346 security components under three different domains such as Business Operation Support Service (BOSS), Information Technology Operation Support (ITOS), and Security and Risk Management (S&RM) and four different service layers such as infrastructure services, information services, application services, and presentation services. Therefore, this is a streamlined, transparent risk management process where the responsibilities are clearly delineated as shown in the table below:

In the above chart, “X” indicates that the respective security component has to be implemented by the actor; “A” indicates that the security component has to be implemented internally; “B” indicates that this is for “business broker only” and there is no direct association with the consumer; blank cell indicates that the security component is not needed for securing the cloud platform.

There is a mapping of security components from the TCI-RA to the NIST 800-53 family of security controls in the “800-53 Family” column in the spreadsheet. In the above example, BOSS→ Compliance→Intellectual Property Protection is mapped to Access Control (AC). Similarly, there is a mapping to Awareness and Training (AT) as well.

Using the above methods, we now have a way to map security components to cloud deployment models with an eye towards which actor is responsible for what.

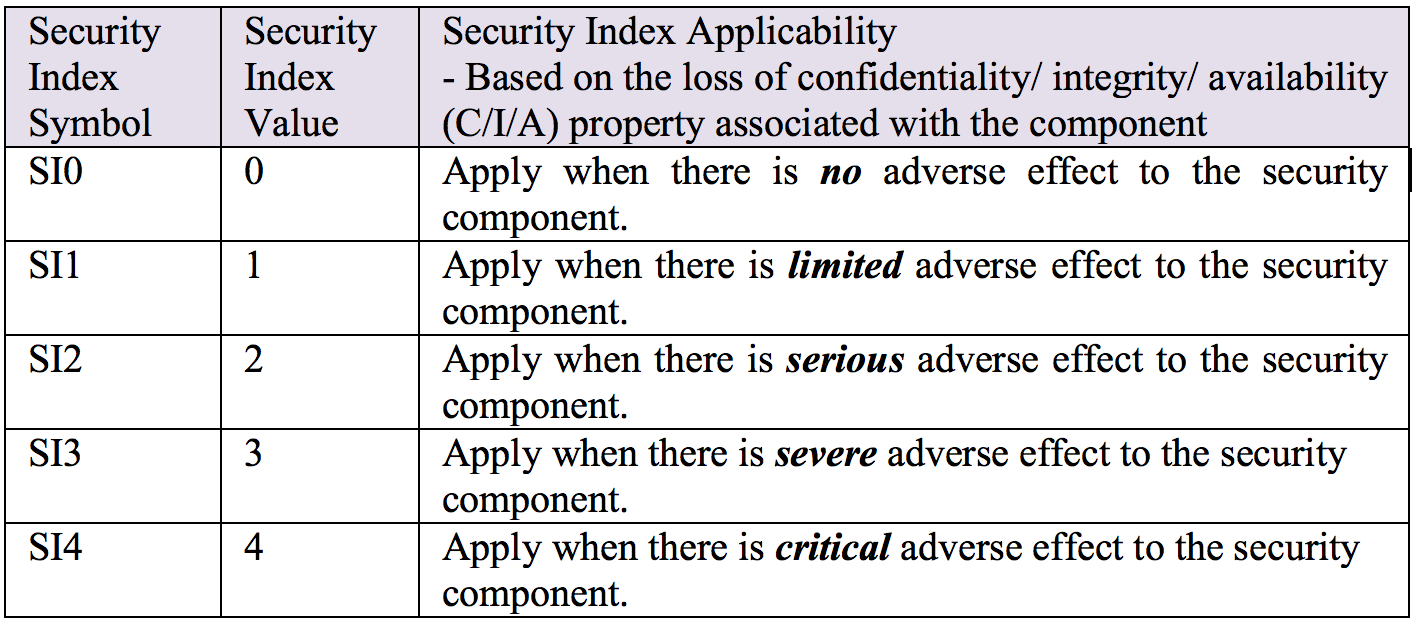

The question now becomes as to what security components are absolutely needed by the consumer to have a secure move to the public cloud. This is where the combination of the last step – categorize information systems – and the security index system (SIS) comes in. SIS defines five index values from zero to four as follows [13]:

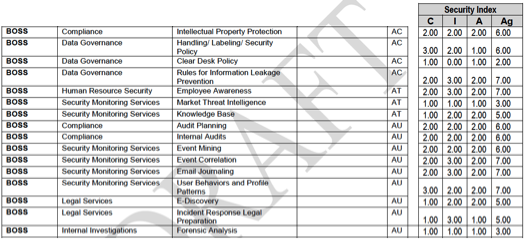

Based on security category obtained from applying step one, the cloud consumer could go on to applying security index values to all the security components as shown below:

* Ag = Aggregate score

By following these steps, all the cloud actors know exactly what security components are needed for the migration and who is responsible for implementing them. This will also give an idea about choosing the right service model (PaaS or SaaS) for the web application in question.

CSA has a specific gap analysis model where the cloud actors could go about selecting the right set of security components for their cloud platform based on their compliance needs such as Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA), Payment Card Industry Data Security Standard (PCI DSS), Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act (GLBA), and Sarbanes Oxley (SOX) etc.

For example, if an organization accepts, captures, stores, transmits, or processes credit/debit card data through one of its e-commerce application, the organization is expected to follow PCI DSS.

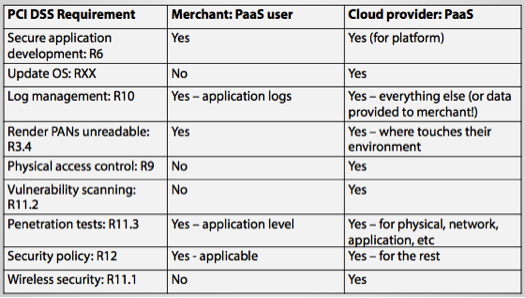

If the organization wants to migrate its application to the public cloud, all the relevant cloud agents – cloud consumer, provider, broker, carrier, and/or auditor – are expected to have all the necessary security components along with the controls in place to support the PCI DSS standard. To conform to PCI DSS standards, the cloud actors have to ensure that the following security components are implemented as follows:

* Merchant = Cloud Consumer; PAN = Personal Access Number

By the same token, similar security requirements can be gathered for HIPAA, GLBA, and SOX.

At the end of step two, all the relevant cloud actors must know the baseline security controls and any supplemental controls needed due to compliance needs of the cloud consumer. The selection of controls could be based on the in-house technical expertise of the cloud consumer along with its assurance needs.

3) Select the Cloud Ecosystem Architecture

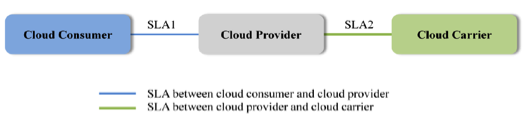

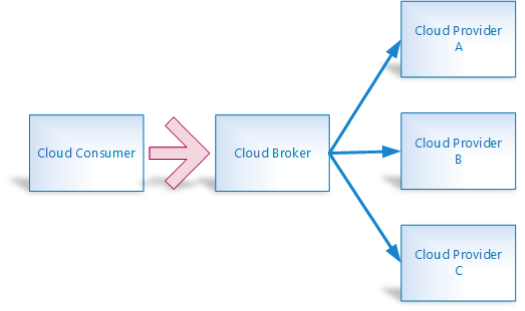

Based on the business requirements and the security requirements outlined in the previous section, a cloud consumer could make a decision to either go with a single cloud provider or a set of cloud providers with the help of a broker as shown in the diagram below:

Imagine a scenario where a consumer is in need of a web content management solution, a video encoding service so the consumer could post videos across a wide variety of social websites such as Facebook, Twitter etc. and a Web development platform based on the “Spring” framework. In order to avail all of the above services, the cloud consumer might need to seek the help of three different cloud providers as follows:

- Cloud Provider A – A SaaS-based Web Content Management Solution. E.g. SpringCM

- Cloud Provider B – A SaaS-based Video Encoding services. E.g. Brightcove

- Cloud Provider C – A PaaS-based Web development platform based on the Spring Framework. E.g. CloudFoundry.

In order to understand and implement all the security controls required to support the assurance needs, the cloud consumer has to deal with multiple Service Level Agreements (SLA) across the various cloud providers. Depending upon the technical expertise and the number of personnel supporting such efforts, the task of managing multiple SLAs could be daunting. This is where cloud brokers come in. As shown in the above figure, the cloud consumer is only signing one SLA with the broker leaving the entire responsibility of managing the business and security requirements across all of the cloud providers with the broker.

4) Assess the Cloud Services

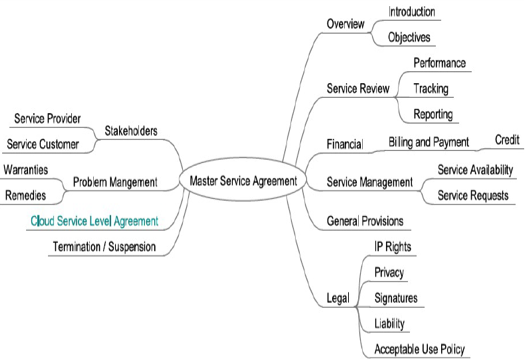

Based on the set of security controls selected in step two and the ecosystem architecture selected in step three, the cloud consumer is well on the way to defining the service level agreement (SLA) with the intended cloud agent(s) – broker or provider(s). The SLA details the levels and types of services that are to be provided, including but not limited to the delivery time and performance parameters. A mind map of an SLA is shown below [13]:

It is the responsibility of the cloud consumer to ensure that default contracts are not accepted when setting up the master service agreements. From a provider’s perspective it may be easy, but the agreement might not capture all of the assurance needs of the consumer.

5) Authorize Cloud Services

In this step, the cloud consumer must define a set of metrics that can validate the expectations defined in the service contract as stated in the previous step. The NIST Cloud Service Metrics document [21] defines a set of metrics for cloud services. An example is as follows:

-

Service Availability – Percentage of uptime of resource over a period of time where:

- For example, the SLA could state that the objective of the service availability metric to be:

A similar set of metrics must be defined in advance to ensure a proper delivery of services by the cloud brokers/providers. For example, “the number of concurrent users and the response time of the platform/service” could be one of the metrics.

6) Monitor the services provided

This is the crucial step to ensuring that the security controls that have been put in place as a part of securing the cloud service are functioning as intended and maintain the necessary security posture. Continuous monitoring enables the cloud agents to supplement security controls in case there is a need. A strategy for continuous monitoring could define as to how security and privacy controls will be monitored over time as follows:

- Frequency of monitoring activities

- Rigor and extent of monitoring activities

- Data feeds to be provided to the consumer

The continuous monitoring strategy allows the consumer to see whether the SLA terms are met on an ongoing basis.

Together, these six steps must be able to prepare an organization to successfully move to the public cloud for their Web application needs.

I’ll contiunue my discussion in the next post.

[11] OSA, “SP-011: Cloud Computing Pattern,” ed, 2013.

[12] NIST. (2011). Guidelines on Security and Privacy in Public Cloud Computing. Available: http://www.nist.gov/customcf/get_pdf.cfm?pub_id=909494

[13] NIST. (2011). NIST Cloud Computing Security Reference Architecture (DRAFT). Available: http://collaborate.nist.gov/twiki-cloud-computing/pub/CloudComputing/CloudSecurity/

NIST_Security_Reference_Architecture_2013.05.15_v1.0.pdf

[14] CSA. (2012). Cloud Controls Matrix v1.4 : Cloud Security Alliance. Available: https://cloudsecurityalliance.org/download/cloud-controls-matrix-v1-4

[15] B. Damele. (2009). Advanced SQL injection to operating system full control. Available: https://http://www.owasp.org/images/d/dc/AppsecEU09-Damele-A-G-Advanced-SQL-injection-slides.pdf

[16] T. Shimeall. (2013). Tactics and Penetration Testing. Available: https://blackboard.andrew.cmu.edu/bbcswebdav/pid-449058-dt-content-rid-3403035_1/xid-3403035_1

[17] T. Shimeall. (2013). Web Hacking. Available: https://blackboard.andrew.cmu.edu/bbcswebdav/pid-449052-dt-content-rid-3403026_1/xid-3403026_1

[18] T. Shimeall. (2013). Strategy. Available: https://blackboard.andrew.cmu.edu/bbcswebdav/pid-449058-dt-content-rid-3403035_1/xid-3403035_1

[19] NIST. (2008). Volume I: Guide for Mapping Types of Information and Information Systems to Security Categories. Available: http://csrc.nist.gov/publications/nistpubs/800-60-rev1/SP800-60_Vol1-Rev1.pdf

[20] NIST. (2006). Minimum Security Requirements for Federal Information and Information Systems Available: http://csrc.nist.gov/publications/fips/fips200/FIPS-200-final-march.pdf

[21] NIST. (2013). NIST Cloud Computing Reference Architecture Cloud Service Metrics Description. Available: http://collaborate.nist.gov/twiki-cloud-computing/pub/CloudComputing/RATax_CloudMetrics_WAs_Docs/RATAX-CloudServiceMetricsDescription-DRAFT-20130621.pdf

[22] SAFECode. (2012). Practical Security Stories and Security Tasks for Agile Development Environments. Available: http://www.safecode.org/publications/SAFECode_Agile_Dev_Security0712.pdf

[23] J. Rockwood, “Choose Your Weapon Wisely: A handbook for determining the right software development method best suited for your team, client, and project (Independent Study Paper). Pittsburgh, PA: School of Computer Science, Carnegie Mellon University,” 2011.

[24] H. Kniberg. (2007). Scrum and XP from the Tenches - How we do Scrum. Available: http://infoq.com/minibooks/scrum-xpfrom-the-trenches

[25] M. Hüttermann, Agile ALM : lightweight tools and Agile strategies. Shelter Island, N.Y.: Manning, 2012.

[26] SecurityNinja. (2009). Secure Development. Available: http://www.securityninja.co.uk/secure-development

[27] OWASP. (2013). Projects/OWASP Java Encoder Project - OWASP. Available: https://http://www.owasp.org/index.php/Projects/OWASP_Java_Encoder_Project

[28] OWASP, “Category:OWASP Enterprise Security API - OWASP,” ed, 2013.

[29] D. Cornell. (2013). Web application testing: The difference between black, gray and white box testing. Available: http://searchsoftwarequality.techtarget.com/tip/Web-application-testing-The-difference-between-black-gray-and-white-box-testing