Continuing from where we left off in Part 2, lets start exploring the usage of the PaaS model in this post.

IV. USING THE PAAS SERVICE MODEL

As illustrated in Who Manages What? in Part 2, the cloud consumer is responsible for the application and data that are deployed on the platform provided by the cloud agent – namely, the broker or the provider. Therefore, the cloud consumer is responsible for implementing the security controls to secure the application and data. A large number of attacks originate in the application layer especially for web applications. The CSA organizes application security into the following areas of focus [4]:

A. Secure Software Development Life Cycle (SSDLC)

B. Authentication, Authorization, Compliance

C. Entitlement Processing and Encryption

D. Application Penetration Testing for the Cloud

E. Monitoring applications in the Cloud

F. Application Authentication, Compliance and the repercussions of multi-tenancy and shared infrastructure

G. Avoiding malicious software

The following section will delve into two major topics:

- Secure application development

- Penetration Tests for the cloud environment

A. Secure Software Development Life Cycle (SSDLC)

A good application security starts early in the software development life cycle. To have a sense of application security throughout the development cycle, it makes a lot of sense to adopt one of the maturity models in the SDLC such as Building Security In Maturity Model (BSIMM), Software Assurance Maturity Model (SAMM), and System Security Engineering Capability Maturity Model (SSE-CMM).

For the purposes of this paper, we will explore the idea of incorporating security into agile development environments especially in Scrum-based web application software development [22].

1) Agile Scrum – a quick introduction

One of the strengths of this process framework is its ability to provide an “early feedback system” thereby an organization building the software can correct its course without spending too much time and money. Since the team developing the software constructs only a portion of the software at a time (a few features at a time), tests them, and deploys them. By deploying in chunks, the organization is able to get a set of early feedback from the marketplace and is able to correct its course.

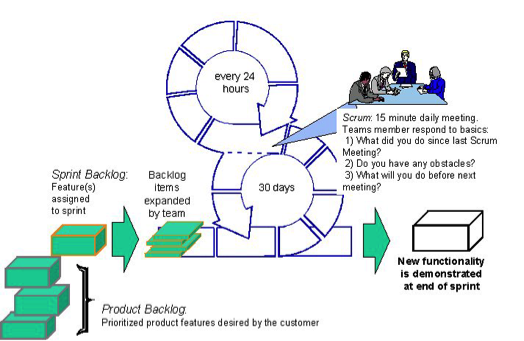

The following section introduces the various elements of the Scrum process from a 1000-foot view:

- The Scrum Team

- Scrum Master

- Person responsible for the Scrum process, its correct implementation, and the maximization of its benefits.

- Not a leader of the team because the team is expected to be self-organizing.

- Responsible for removing any impediments between the development team, product owner, and customers.

- Product Owner (PO)

- A person responsible for managing the product backlog in terms of priority

- Development Team

- Scrum team consists of 2-7 developers.

- The team makes decisions during the development in conjunction with the product owner.

- When there is a need for a bigger team (>7), split them to form multiple teams based on themes or epics.

- Scrum Master

- Artifacts

- User Story

- A simple descriptive line of the requirement or feature that the PO is after. E.g. “Charge customer’s credit/debit card for the services rendered”.

- Epic

- A set of user stories. For example, an epic could be about “Online Payment processing”.

- Product Backlog

- Backlog is a prioritized list of project requirements or user stories or Epics with rough estimates. Estimates are based on story points.

- An example of a story point could equate to an ideal man-day where the day is devoid of any external influences so that the developer could concentrate on the task 100%.

- The list is sorted based on estimates in descending order.

- Backlog is a prioritized list of project requirements or user stories or Epics with rough estimates. Estimates are based on story points.

- Sprint Backlog

- A set of project requirements taken from the product backlog to be worked on during a specific Sprint.

- User Story

- Scrum Events

- Sprint

- Sprint is a period of time, a time box, that the team is expected to work on the Sprint backlog.

- Typically, 2-4 week sprints are common.

- Daily Scrum Meetings

- Fifteen minute standup meeting to discuss the following items:

- Accomplishments from the last meeting.

- What is slated to be done before the next meeting

- Any impediments to be removed for project progress.

- Fifteen minute standup meeting to discuss the following items:

- Sprint Planning Meetings

- PO presents the high priority items to the team

- The team decides as to what can or cannot be done during a particular sprint with an action plan document.

- Typically, the team attempts to split the user story into multiple tasks at this meeting.

- Security-focused stories and tasks are discussed and included.

- Sprint Review meeting or Demo

- During this meeting, the team demonstrates all the completed features that are part of a sprint.

- Sprint Retrospective meeting

- The team discusses “Lessons learned” during the Sprint.

- Sprint

By following the process flow, the development team in conjunction with the Scrum Master and the Product Owner is able to engage in constant communication (informal) to properly handle requirements elicitation/analysis and subsequently the product feature code development and deployment.

2) Missing Security Focus in Agile Scrum

Though not a fault of the process framework, the emphasis on quick turn-around of feature implementation doesn’t help either. Since the “Sprints” are typically time-boxed between 2 and 4 weeks, developers often ignore application security controls or put them on the back burner. Since the PO is more interested in shipping the product with a heavy focus on business functionality, there is no step to ensure security controls are put in place by enforcing that the security requirements are captured in the stories and security-focused tasks are performed during the construction and testing phases of each story.

3) Securing the SDLC in Agile Scrum

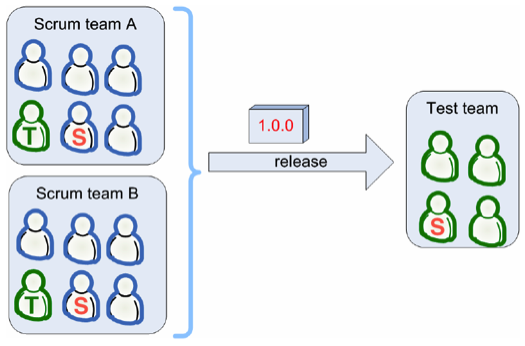

As explained in the previous section, the development team constructs a set of user stories at a time (sprint backlog within 2-4 week sprints). To have a constant security awareness, user story after user story and Sprint after Sprint, it makes a lot of sense to have a permanent security-focused member on the team as shown in the following diagram – adapted from [24]:

* T – member with testing skills; S – member with Security skills

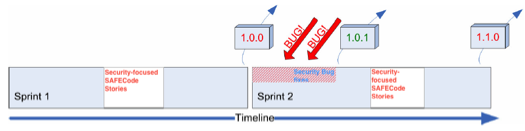

Along with regular functionality testing, the QA team can also test for security issues and send the release back to the development team for fixes as shown in the diagram below – adapted from [24]:

- A portion of the Sprint is dedicated to implementing SAFECode stories

- This can be accomplished by adjusting the focus factor if the PO and the stakeholders don’t fully understand the security implications.

- A portion of bug-fixes address security vulnerabilities found during QA testing

The responsibility of the team member will entail the following:

- Conduct security analysis of all product features in the Sprint backlog

- Conduct a threat model for each user story

- Security aspects to be considered, including but not limited to policy/compliance, legal, contractual, regulatory, and other security-related requirements

- Notify the PO of the security requirements in the Sprint planning meeting

- Engage the Scrum master to work with legal and other departments to ensure security obligations are properly met.

- Adjust the story points of the stories/epics accordingly

- User stories that have security implications would need to have additional tasks defined to cater to the implementation of security controls.

- Ensure that the Sprint doesn’t collect “Security Debt” [22] as a team

- If the application has to ship with some security debt, ensure that the relevant stakeholders understand the risks and sign off on them

- Undone security tasks must go on the product backlog, so they can be included in one of the future Sprints.

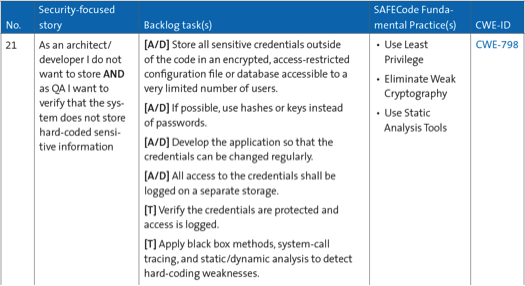

4) SAFECode guidelines for the Scrum team

SAFECode has defined a set of 36 security-focused stories with a breakdown of technical tasks that go along with each story. These stories are meant for the development and QA teams. One of the stories from the SAFECode guidelines is shown below:

5) SAFECode guidelines for the Scrum team as software maintenance tasks

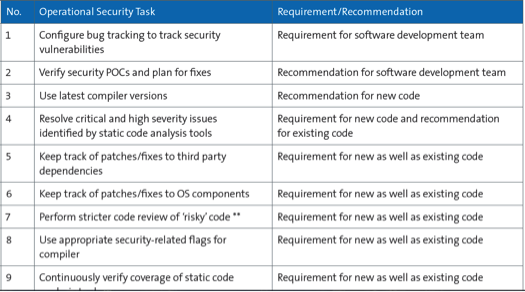

The idea here is to periodically run static code analysis tools, vulnerability scanners, and automated malware scanners during build/release cycles and fix the reported high-priority issues reported by those tools. Some of the guidelines provided by SAFECode are shown below:

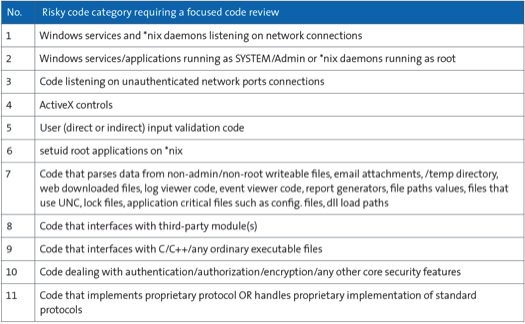

It is also important to allocate time to do “code reviews” of riskier codes. SAFECode provides the definition of riskier code as follows:

As shown in the previous sections, the Agile Scrum process could be made secure. The PO has to have visibility into these security tasks, as performing some of these security-focused tasks would impact the team’s velocity. In order for the SDLC to be secure and to ensure that the product that is put out Sprint after Sprint is secure, the team needs support from all the stakeholders especially from the line of business managers, IT functional managers, Chief Information Officer (CIO), Chief Information Security Officer (CISO), and in some cases the support of the Chief Executive Officer (CEO).

I’ll contiunue my discussion in the next post.

[11] OSA, “SP-011: Cloud Computing Pattern,” ed, 2013.

[12] NIST. (2011). Guidelines on Security and Privacy in Public Cloud Computing. Available: http://www.nist.gov/customcf/get_pdf.cfm?pub_id=909494

[13] NIST. (2011). NIST Cloud Computing Security Reference Architecture (DRAFT). Available: http://collaborate.nist.gov/twiki-cloud-computing/pub/CloudComputing/CloudSecurity/

NIST_Security_Reference_Architecture_2013.05.15_v1.0.pdf

[14] CSA. (2012). Cloud Controls Matrix v1.4 : Cloud Security Alliance. Available: https://cloudsecurityalliance.org/download/cloud-controls-matrix-v1-4

[15] B. Damele. (2009). Advanced SQL injection to operating system full control. Available: https://http://www.owasp.org/images/d/dc/AppsecEU09-Damele-A-G-Advanced-SQL-injection-slides.pdf

[16] T. Shimeall. (2013). Tactics and Penetration Testing. Available: https://blackboard.andrew.cmu.edu/bbcswebdav/pid-449058-dt-content-rid-3403035_1/xid-3403035_1

[17] T. Shimeall. (2013). Web Hacking. Available: https://blackboard.andrew.cmu.edu/bbcswebdav/pid-449052-dt-content-rid-3403026_1/xid-3403026_1

[18] T. Shimeall. (2013). Strategy. Available: https://blackboard.andrew.cmu.edu/bbcswebdav/pid-449058-dt-content-rid-3403035_1/xid-3403035_1

[19] NIST. (2008). Volume I: Guide for Mapping Types of Information and Information Systems to Security Categories. Available: http://csrc.nist.gov/publications/nistpubs/800-60-rev1/SP800-60_Vol1-Rev1.pdf

[20] NIST. (2006). Minimum Security Requirements for Federal Information and Information Systems Available: http://csrc.nist.gov/publications/fips/fips200/FIPS-200-final-march.pdf

[21] NIST. (2013). NIST Cloud Computing Reference Architecture Cloud Service Metrics Description. Available: http://collaborate.nist.gov/twiki-cloud-computing/pub/CloudComputing/RATax_CloudMetrics_WAs_Docs/RATAX-CloudServiceMetricsDescription-DRAFT-20130621.pdf

[22] SAFECode. (2012). Practical Security Stories and Security Tasks for Agile Development Environments. Available: http://www.safecode.org/publications/SAFECode_Agile_Dev_Security0712.pdf

[23] J. Rockwood, “Choose Your Weapon Wisely: A handbook for determining the right software development method best suited for your team, client, and project (Independent Study Paper). Pittsburgh, PA: School of Computer Science, Carnegie Mellon University,” 2011.

[24] H. Kniberg. (2007). Scrum and XP from the Tenches - How we do Scrum. Available: http://infoq.com/minibooks/scrum-xpfrom-the-trenches

[25] M. Hüttermann, Agile ALM : lightweight tools and Agile strategies. Shelter Island, N.Y.: Manning, 2012.

[26] SecurityNinja. (2009). Secure Development. Available: http://www.securityninja.co.uk/secure-development

[27] OWASP. (2013). Projects/OWASP Java Encoder Project - OWASP. Available: https://http://www.owasp.org/index.php/Projects/OWASP_Java_Encoder_Project

[28] OWASP, “Category:OWASP Enterprise Security API - OWASP,” ed, 2013.

[29] D. Cornell. (2013). Web application testing: The difference between black, gray and white box testing. Available: http://searchsoftwarequality.techtarget.com/tip/Web-application-testing-The-difference-between-black-gray-and-white-box-testing